22. NLP - Basic Techniques to Analyze Text Data#

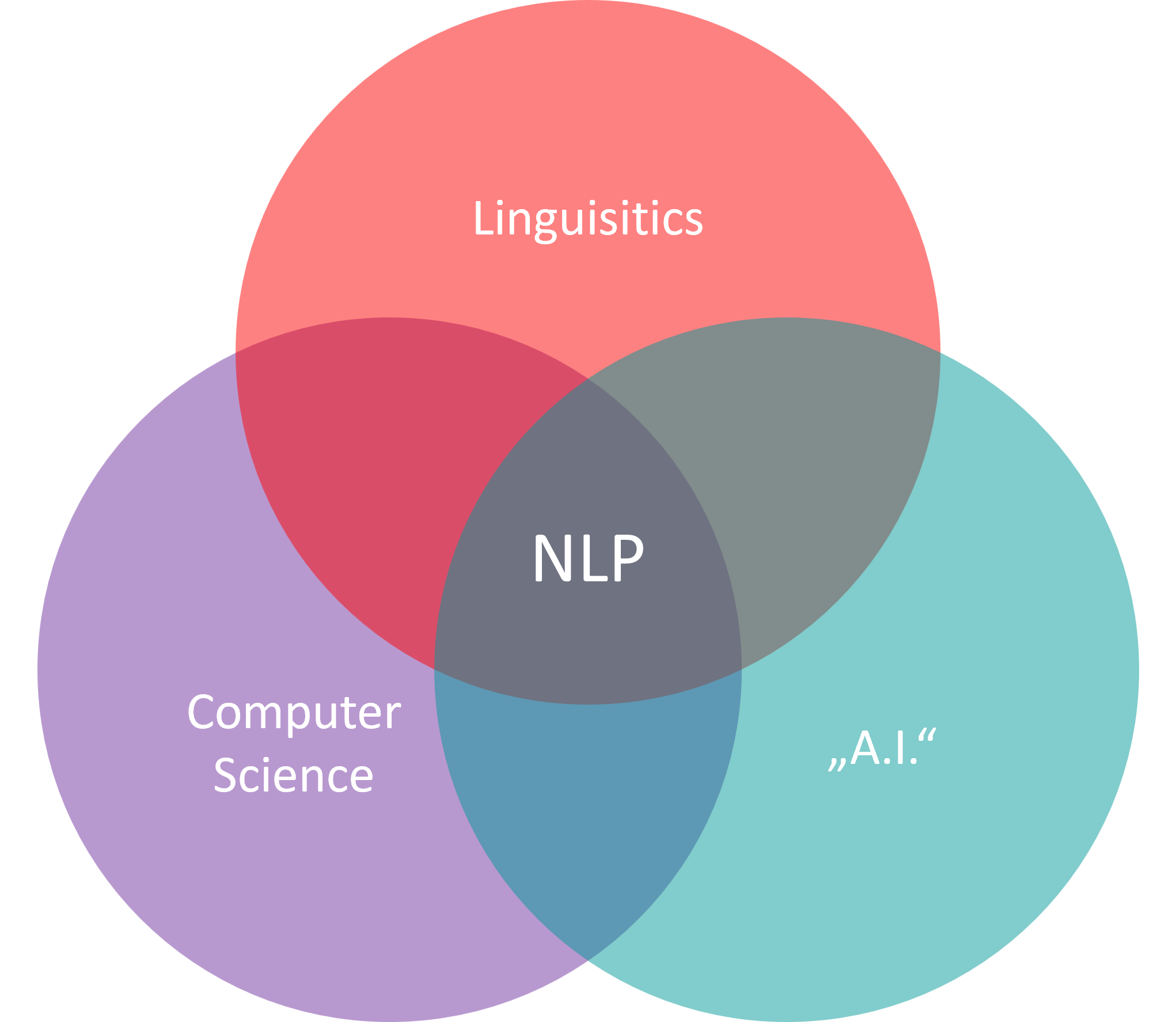

Natural Language Processing (NLP) is an interdisciplinary field at the intersection of computer science, artificial intelligence, and linguistics. It focuses on enabling computers to process, interpret, and derive meaning from human language (see Fig. 22.1). A central objective of NLP is to develop systems capable of “reading” and “understanding” text in order to perform tasks such as translation, summarization, sentiment analysis, and information extraction.

Fig. 22.1 Yes, again a Venn diagram. This time to illustrate that NLP is a highly interdisciplinary field with roots in computer science, AI, but also linguistics.#

The importance of NLP in data science cannot be overstated. Every day, individuals and organizations generate massive volumes of text, ranging from social media updates and product reviews to customer support tickets and emails. NLP provides the tools and techniques necessary to make sense of this data in an automated or semi-automated fashion. By transforming unstructured text into structured data, NLP allows us to analyze and extract insights from human language, providing valuable context to support decision-making processes.

Because NLP encompasses a broad set of methods (from rule-based pattern matching to modern neural language models), this chapter will introduce only the foundational techniques most commonly used in data science workflows. Our goal is to equip you with the basic tools needed to preprocess text, represent it numerically, and perform simple analyses.

22.1. Example areas for the use of NLP techniques#

The following examples illustrate how broadly NLP can be applied and why it is so valuable:

Text Classification

Text classification automatically assigns predefined categories or tags to text. By analyzing content and learning patterns, it streamlines tasks such as spam detection, news topic labeling, and document organization.Sentiment Analysis

Sentiment analysis uses NLP to detect and quantify the emotional tone of a text. Businesses rely on this technique to gauge customer opinions in reviews, social media posts, or survey responses, helping them make informed decisions based on positive, neutral, or negative sentiment.Summarizationg

Summarization distills lengthy documents into concise versions that preserve key points. It can be extractive (selecting important sentences) or abstractive (generating new summary sentences).Spell Checking

Spell-checking tools detect and suggest corrections for misspelled words. Modern approaches go beyond simple dictionary lookups by using context-aware models (e.g., probabilistic or neural methods) to correct typos or wrong word choices (e.g., “their” vs. “there”), which improves clarity and credibility in written text.Machine Translation

Machine translation (MT) converts text from one language to another. Contemporary MT systems—often based on neural sequence-to-sequence architectures—handle idiomatic expressions and context far better than older rule-based or phrase-based methods. MT accelerates multilingual communication, making large volumes of content accessible across languages.Chatbots

Chatbots leverage NLP to understand user queries, infer intent, and generate appropriate replies in real time. They combine components such as intent classification, entity recognition, dialogue management, and response generation. Modern chatbots are, for instance, used to handle customer service, information retrieval, and even casual conversation.

22.2. Python NLP libraries#

There are several Python libraries that are popularly used for modern Natural Language Processing (NLP) tasks. Here are a few of the most commonly used ones:

NLTK (Natural Language Toolkit): This is a widely used library for symbolic and statistical NLP. It provides easy-to-use interfaces to over 50 corpora and lexical resources, such as WordNet. NLTK also includes text processing libraries for classification, tokenization, stemming, tagging, parsing, and semantic reasoning. It’s excellent for teaching and working with the basics of NLP.

SpaCy: This library is known for its advanced NLP capabilities and efficient performance. SpaCy is designed to handle large volumes of text, and its features include named entity recognition, part-of-speech tagging, dependency parsing, and sentence segmentation. Its flexibility and speed make it ideal for production-grade NLP tasks [Vasiliev, 2020].

Gensim: This is a robust open-source vector space modeling and topic modeling toolkit. Gensim is designed to handle large text collections using data streaming and incremental algorithms, which is different from most other scientific software packages that only target batch and in-memory processing. It is especially good for tasks that involve topic modeling and document similarity analysis.

TextBlob: This library simplifies text processing tasks by providing a consistent API for diving into common NLP tasks such as part-of-speech tagging, noun phrase extraction, sentiment analysis, and more. TextBlob is very beginner-friendly and is an excellent choice for basic NLP tasks and for people getting started with NLP in Python.

Transformers (by Hugging Face): This library is based on the transformer architecture (like BERT, GPT, RoBERTa, XLM, etc) and has pre-trained models for many NLP tasks. It offers simple, yet powerful, APIs for performing tasks such as text classification, named entity recognition, translation, summarization, and more. It is a go-to library for state-of-the-art NLP (but clearly beyond the NLP basics that we will cover here).

Here, we will work with SpaCy and NLTK.

#!pip install nltk

#!pip install spacy

import os

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

# NLP related libraries to work with text data

import nltk

import spacy

22.3. NLP Preprocessing Workflow#

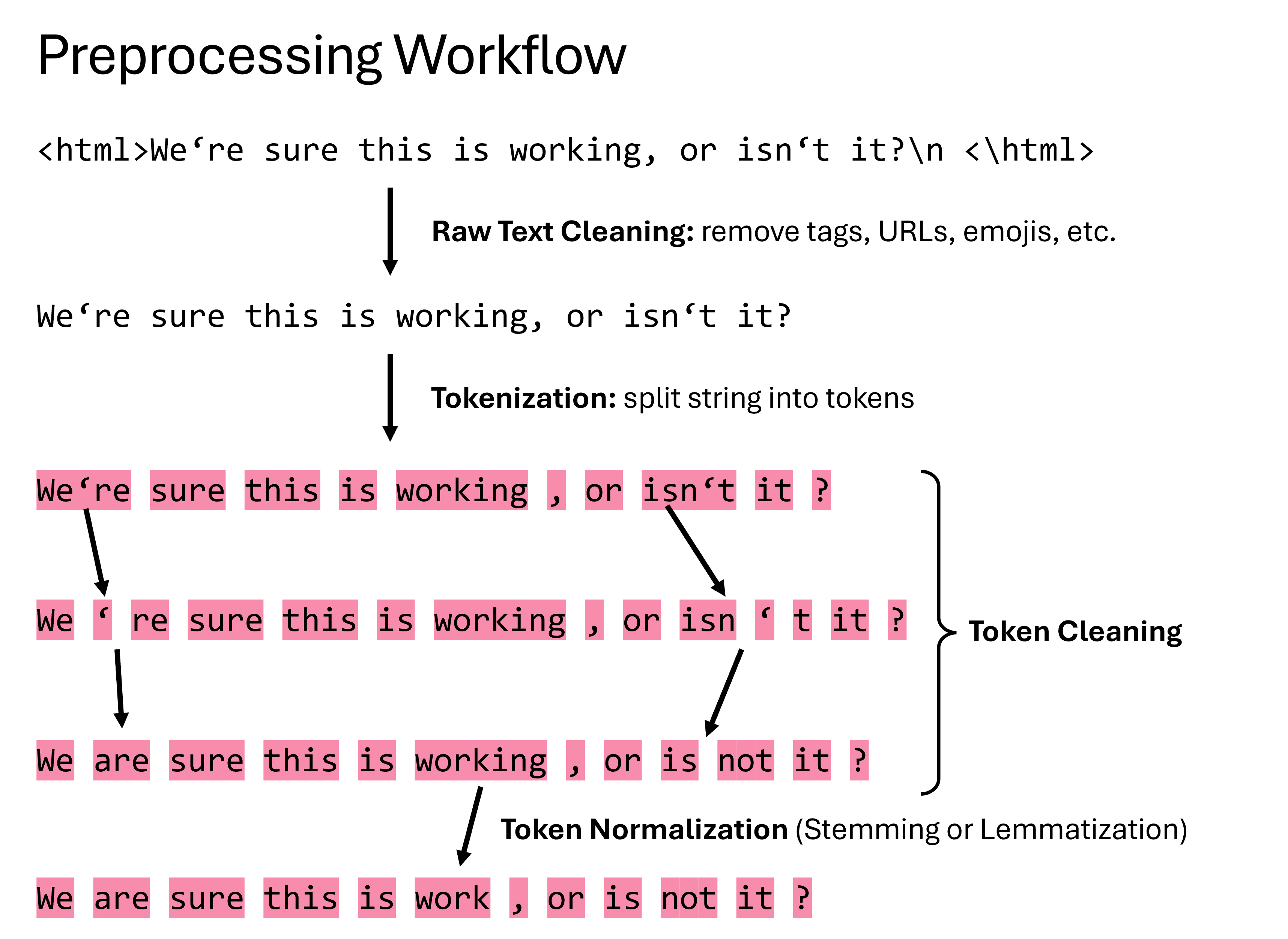

We usually work with text in various formats and sizes, for instance, from .txt, .html, or other structured or unstructured text file formats. For a later systematic data analysis or the training of machine-learning models, we first have to preprocess the text data consistently, typically done as sketched in Fig. 22.2.

Fig. 22.2 Typically, an NLP preprocessing workflow consists of several stages, including raw text cleaning, tokenization, token cleaning, and token normalization. This is often the basis for later analysis or modeling steps.#

22.3.1. Raw Text Cleaning#

When you obtain or scrape text from various sources (web pages, PDFs, social media, logs), it often contains “noise” that can hinder analysis:

HTML/XML tags and markup: Words mixed with

<p>,<div>, or other tags become fragmented tokens unless those tags are removed first.URLs, email addresses, and file paths: Raw links (e.g.,

https://…) or email strings (foo@example.com) tend to inflate your vocabulary with nonsensical tokens.Irregular whitespace: Multiple spaces, tabs, or stray line breaks can lead to empty or malformed tokens.

Mixed casing and punctuation: “DataScience,” “Data Science,” and “data science” may all appear separately unless you normalize case and handle punctuation uniformly.

Contractions, emojis, and special characters: In user‐generated content (tweets, reviews), apostrophes (“don’t”), emoticons (”😊”), or accented letters can either be informative or troublesome, depending on the task.

The goal of raw‐text cleaning is to strip away or standardize these unwanted elements so that what remains is plain, continuous text composed of meaningful characters. In practice, cleaning might involve:

Removing or replacing HTML/XML tags (so that

<strong>Bold</strong>becomes simply “Bold”).Stripping out URLs and email patterns (or substituting them with placeholder tokens like

<URL>or<EMAIL>if you want to preserve their presence).Collapsing multiple spaces/newlines into single spaces.

Converting all characters to lowercase (unless you plan to preserve casing for named‐entity recognition or similar tasks).

Handling punctuation—either by removing most punctuation marks or by preserving certain symbols (like apostrophes) until the tokenization step.

By cleaning first, you avoid feeding spurious tokens (e.g., "<a>", "http://…", or stray “—”) into your tokenization process. Clean text provides a stable foundation for the next stage.

22.3.2. Tokenization#

Once the text is “clean” (i.e., markup removed, URLs taken out, whitespace normalized, and casing standardized), the next step is to split it into discrete units called tokens. Tokens typically represent words, but depending on your approach, they can also be punctuation marks, subwords, or even entire sentences.

Word‐Level Tokenization At its simplest, you break a cleaned string on spaces to get individual words. In practice, however, you often rely on more robust tokenizers that handle punctuation attached to words (e.g.,

"hello!" → ["hello", "!"]) and contractions ("don’t" → ["do", "n’t"]). The key point is that tokenization turns a long string into a list of word‐like elements you can process one at a time.Sentence‐Level Tokenization (Optional) Some applications—such as summarization or sentiment analysis at the sentence level—require you to split a text into sentences before tokenizing words. In that case, you first identify sentence boundaries (e.g., by looking for periods, question marks, or line breaks) and then tokenize each sentence separately.

Subword or Character‐Level Tokenization (Beyond Basics) For many modern neural models, individual words are further split into subword units (e.g., “running” → [“run”, “##ning”]) or even individual characters. This helps handle rare or out‐of‐vocabulary words. We will cover those approaches in later chapters; for now, assume that tokens correspond roughly to English words or punctuation.

After tokenization, you have a sequence such as:

["this", "is", "an", "example", "sentence", ".", "it", "contains", "punctuation", "and", "mixed", "case", "."]

Each of these tokens can now be examined, counted, or transformed in isolation.

22.3.3. Token Cleaning & Normalization#

Even after tokenization, many tokens still need further refinement before they become truly useful for feature extraction or modeling. Token cleaning and normalization typically include:

Lowercasing (if not already applied globally) Ensures that “Data” and “data” are treated identically rather than as two separate tokens.

Punctuation Stripping or Filtering If punctuation was not fully removed during raw‐text cleaning, you may drop tokens that consist only of punctuation (e.g., “.”, “,”, “!”). Alternatively, you can strip punctuation characters from the beginnings or ends of word tokens (e.g.,

"science," → "science"). Be careful: sometimes punctuation conveys meaning (e.g., “U.S.A.” or “C++”), so decide based on your specific use case.Stop‐Word Removal (Optional) Common words like “the,” “and,” “to,” and “is” often appear so frequently that they contribute little to distinguishing meaning in tasks like topic classification. By removing these stop words, you reduce noise and shrink the vocabulary. However, for certain tasks (e.g., sentiment analysis or author attribution), you might retain pronouns and auxiliary verbs because they can carry important signals.

Digit and Special‐Character Handling (Optional) Some pipelines remove tokens that contain digits (e.g., “2025” or “A1B2”), replace them with a

<NUM>placeholder, or leave them intact if numeric information is relevant (e.g., product codes, dates).Contraction Expansion (If Deferred) If you did not expand contractions during raw‐text cleaning, you can handle them at this stage. For example, mapping “don’t” → “do not” ensures that both “do” and “not” become separate, meaningful tokens rather than

"don’t"which may not appear in your vocabulary.

After token cleaning, your list of tokens might look like:

["this", "example", "sentence", "contains", "punctuation", "mixed", "case"]

Notice that casing has been unified, purely punctuation tokens have been removed, and any stop words (e.g., “is”, “an”, “and”) have been dropped. At this point, each token represents a distilled, meaningful unit ready for the next stages—such as converting to stems or lemmas, computing frequency counts, or feeding into a vectorization algorithm.

22.3.4. How These Stages Fit Together#

Raw Text Cleaning • Strips away extraneous markup, URLs, and inconsistent spacing. • Produces one long, lowercase string of “plain” text.

Tokenization • Splits the cleaned string into atomic units (tokens). • Creates a sequence (list) of tokens that still reflect some noise (e.g., punctuation, stop words).

Token Cleaning & Normalization • Further purifies tokens by removing punctuation‐only tokens, lowercasing (if needed), filtering out stop words, and handling numbers or contractions. • Yields a final list of tokens that are consistent, comparable, and ready for stemming, lemmatization, or direct feature extraction.

This entire process allows us to transform raw text data into a more digestible and analyzable format, preparing the ground for more advanced NLP techniques.

nltk.download('wordnet')

#nltk.download('omw-1.4')

#nltk.download('punkt')

[nltk_data] Downloading package wordnet to /home/runner/nltk_data...

True

22.4. NLTK#

Here, we demonstrate the NLTK processes of tokenization, stemming, and lemmatization.

22.4.1. Tokenization#

Tokenization is the process of splitting a large paragraph or text into sentences or words. These sentences or words are known as tokens. This is a crucial step in NLP as we often deal with words in text data.

In this block of code, we import NLTK and define a string of text. The text contains a list of words with different grammatical forms. Using NLTK’s TreebankWordTokenizer, we break down the text into individual words, or “tokens”. The output is a list of these tokens.

text = "feet cats wolves talking talked?"

tokenizer = nltk.tokenize.TreebankWordTokenizer()

tokens = tokenizer.tokenize(text)

print(tokens)

['feet', 'cats', 'wolves', 'talking', 'talked', '?']

22.4.2. Stemming#

Stemming is a process of reducing inflected (or sometimes derived) words to their word stem or root form—generally a written word form. The stem need not be identical to the morphological root of the word.

Here, we create a PorterStemmer object and use it to find the root stem of each word in our list of tokens. The result is a list of these stems. You’ll notice that the stems aren’t always valid words (like ‘wolv’ for ‘wolves’), as stemming operates on a rule-based approach without understanding the context.

stemmer = nltk.stem.PorterStemmer()

print([stemmer.stem(w) for w in tokens])

['feet', 'cat', 'wolv', 'talk', 'talk', '?']

22.4.3. Lemmatization#

Lemmatization is the process of reducing inflected words to their word base or dictionary form. It’s similar to stemming but is more accurate as it takes the context and meaning of the word into consideration.

Instead of the PorterStemmer, we use NLTK’s WordNetLemmatizer to find the dictionary base form (or lemma) of each word. This results in a list of lemmas. As you can see, lemmatization provides a more accurate root form (‘wolf’ for ‘wolves’) as compared to stemming.

stemmer = nltk.stem.WordNetLemmatizer()

print([stemmer.lemmatize(w) for w in tokens])

['foot', 'cat', 'wolf', 'talking', 'talked', '?']

22.5. NLP for languages other than English#

Natural Language Processing (NLP) is a truly global discipline, extending its reach to languages far beyond just English.

However, it’s worth noting that the effectiveness and ease of applying NLP techniques may vary across languages. For instance, languages with complex morphology like Finnish or Turkish, or those with little word delimitation like Chinese, can present unique challenges. Furthermore, resources and pre-trained models, especially those for machine learning, are more readily available for some languages, particularly English, than for others.

22.5.1. Let’s try some German#

text = "Füsse Katzen Wölfe sprechen gesprochen?" # Not an actual German sentence. Only some words for illustrative purposes.

tokenizer = nltk.tokenize.TreebankWordTokenizer()

tokens = tokenizer.tokenize(text)

tokens

stemmer = nltk.stem.SnowballStemmer("german")

print([stemmer.stem(token) for token in tokens])

['fuss', 'katz', 'wolf', 'sprech', 'gesproch', '?']

22.6. Applying SpaCy Models for Lemmatization#

SpaCy is a highly versatile and efficient Python library for Natural Language Processing (NLP). It offers comprehensive and advanced functionalities, outperforming NLTK in terms of efficiency and speed. You can find extensive details in SpaCy’s official documentation.

Having familiarized ourselves with the concept of lemmatization, let’s now explore its practical application using SpaCy.

Initially, you need to ensure that SpaCy and the relevant language models are installed in your environment. In the case of English, en_core_web_sm is a suitable model, whereas for German, de_core_news_sm can be utilized. SpaCy offers a variety of models for different languages which you can explore on the SpaCy models page.

Installation of SpaCy and downloading of language models can be performed via the following terminal commands:

pip install spacy

python -m spacy download en_core_web_sm

python -m spacy download de_core_news_sm

Download the required language models first:

try:

# Check if already installed

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm")

except:

# If not, download the model

!python -m spacy download en_core_web_sm

# There are many other models, here a small model for German:

#!python -m spacy download de_core_news_sm

Collecting en-core-web-sm==3.8.0

Downloading https://github.com/explosion/spacy-models/releases/download/en_core_web_sm-3.8.0/en_core_web_sm-3.8.0-py3-none-any.whl (12.8 MB)

?25l ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ 0.0/12.8 MB ? eta -:--:--

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ 12.8/12.8 MB 159.6 MB/s eta 0:00:00

?25h

Installing collected packages: en-core-web-sm

Successfully installed en-core-web-sm-3.8.0

✔ Download and installation successful

You can now load the package via spacy.load('en_core_web_sm')

Now that the models are installed, we can load the desired one:

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm")

Let’s now define a text and pass it through the loaded model:

text = "Feet cats wolves, speak, spoken?"

doc = nlp(text) # create NLP object

print(doc)

Feet cats wolves, speak, spoken?

# Or, try an example in German:

#nlp = spacy.load('de_core_news_lg') # large german language model

#nlp = spacy.load('de_core_news_sm') # small german lanugage model

#text = "Füsse Katzen Wölfe sprechen gesprochen?"

#doc = nlp(text) # create NLP object

#print(doc)

22.6.1. Tokenization#

By passing the text through the loaded NLP model, SpaCy already performs tokenization and a host of other operations under the hood:

[token.text for token in doc]

['Feet', 'cats', 'wolves', ',', 'speak', ',', 'spoken', '?']

22.6.2. Lemmatization#

Unlike NLTK, SpaCy has not option for stemming. But it provides many different language models (for many different languages) that allow for good lemmatization.

[token.lemma_ for token in doc]

['foot', 'cat', 'wolf', ',', 'speak', ',', 'speak', '?']

Each word in the text is replaced with its base form or lemma, taking into account its usage in the sentence. This helps in text normalization, a critical step in text preprocessing for NLP tasks.

22.7. Apply tokenization and lemmatization#

“War of the worlds” von H.G. Wells

In the following, we will work with the text of the book “War of the Worlds” from H.G. Wells which is freely available via the Gutenberg Project.

# Define the filename and open the file

filename = "../datasets/wells_war_of_the_worlds.txt"

with open(filename, "r", encoding="utf-8") as file:

text = file.read()

# Perform some basic cleaning: replace newline characters with spaces

text = text.replace("\n", " ")

# How many characters?

len(text)

338168

# Have a look at the first part of the text

text[:1000]

'The Project Gutenberg eBook of The War of the Worlds, by H. G. Wells This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook. Title: The War of the Worlds Author: H. G. Wells Release Date: July 1992 [eBook #36] [Most recently updated: November 27, 2021] Language: English *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE WAR OF THE WORLDS *** cover The War of the Worlds by H. G. Wells ‘But who shall dwell in these worlds if they be inhabited? . . . Are we or they Lords of the World? . . . And how are all things made for man?’ KEPLER (quoted in _The Anatomy of Melan'

# Load the English language model

nlp = spacy.load('en_core_web_sm')

# Create an NLP object by processing the text

doc = nlp(text)

# Tokenization: split the text into individual tokens (words)

tokens = [token.text for token in doc]

print(tokens[:20])

['The', 'Project', 'Gutenberg', 'eBook', 'of', 'The', 'War', 'of', 'the', 'Worlds', ',', 'by', 'H.', 'G.', 'Wells', ' ', 'This', 'eBook', 'is', 'for']

Now that we have all tokens of our book, we can obviously count the number of tokens (which is not the number of words!). But we can also look at how many different tokens there are by using the Python set() function.

# Print the total number of tokens and the number of unique tokens

print(f"Total tokens: {len(tokens)}")

print(f"Unique tokens: {len(set(tokens))}")

Total tokens: 71440

Unique tokens: 7292

Let us now do the same, but with lemmatization.

# Lemmatization: reduce each token to its base or root form

lemmas = [token.lemma_ for token in doc]

print(lemmas[:40])

['the', 'Project', 'Gutenberg', 'eBook', 'of', 'the', 'War', 'of', 'the', 'Worlds', ',', 'by', 'H.', 'G.', 'Wells', ' ', 'this', 'eBook', 'be', 'for', 'the', 'use', 'of', 'anyone', 'anywhere', 'in', 'the', 'United', 'States', 'and', 'most', 'other', 'part', 'of', 'the', 'world', 'at', 'no', 'cost', 'and']

We can also select tokens more specifically by using one of many attributes or methods from SpaCy (see documentation).

For instance:

.is_punctreturnsTrueif a token is a punctuation..is_alphareturnsTrueif a token contains alphabetic characters.is_stopreturnsTrueif word belongs to a so called “stop list” (less important words, we will come to this later)

Since we here only want to count words:

lemmas = [token.lemma_ for token in doc if token.is_alpha]

print(lemmas[:40])

['the', 'Project', 'Gutenberg', 'eBook', 'of', 'the', 'War', 'of', 'the', 'Worlds', 'by', 'Wells', 'this', 'eBook', 'be', 'for', 'the', 'use', 'of', 'anyone', 'anywhere', 'in', 'the', 'United', 'States', 'and', 'most', 'other', 'part', 'of', 'the', 'world', 'at', 'no', 'cost', 'and', 'with', 'almost', 'no', 'restriction']

# Print the total number of lemmas and the number of unique lemmas

print(f"Total lemmas: {len(lemmas)}")

print(f"Unique lemmas: {len(set(lemmas))}")

Total lemmas: 60629

Unique lemmas: 5587

By doing this, we are effectively shrinking the size of the dataset we are working with, while still retaining the essential meaning. It’s worth noting that we also removed “stop words” - common words such as “and”, “the”, “a” - during lemmatization, which usually do not contain important information and are often removed in NLP.

In the following steps, we could now investigate which words are the most common ones, we could identify named entities (such as people or places) or use this text data to train a machine learning model (like a text classifier or a sentiment analysis model).

22.8. Mini-Exercise!#

Why do we get more tokens than lemmas? Have a look at both and find the answer!

22.9. Search specific word types or combinations#

With Spacy we can in principle also do more complex searches. We could, for instance search for nouns, verbs, or adjectives.

nouns = [token for token in doc if token.pos_ == "NOUN"]

print(nouns[:40])

[use, parts, world, cost, restrictions, terms, online, laws, country, Title, Author, eBook, Language, START, PROJECT, WORLDS, worlds, things, man, Contents, BOOK, MARTIANS, CHOBHAM, FIGHTING, DESTRUCTION, XIII, EXODUS, THUNDER, CHILD, BOOK, MARTIANS, FOOT, DAYS, DEATH, WORK, DAYS, IX, COMING, MARTIANS, years]

But we cannot only search all nouns or verbs, but also for specific combinations. As an example, we can search for all combinations of likeor love with a noun:

from spacy.matcher import Matcher

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm")

matcher = Matcher(nlp.vocab)

pattern = [{"LEMMA": {"IN": ["like", "love"]}},

{"POS": "NOUN"}]

matcher.add("like/love", [pattern])

matches = matcher(doc)

for match_id, start, end in matches:

string_id = nlp.vocab.strings[match_id] # Get string representation

span = doc[start:end] # The matched span

print(string_id, start, end, span.text)

like/love 4797 4799 like end

like/love 6222 6224 like eyes

like/love 8394 8396 like object

like/love 8970 8972 like water

like/love 9644 9646 like puffs

like/love 12536 12538 like summer

like/love 16160 16162 like daylight

like/love 19145 19147 like parade

like/love 21471 21473 like distance

like/love 23134 23136 like thunderclaps

like/love 29624 29626 like men

like/love 32952 32954 like forms

like/love 33577 33579 like ghosts

like/love 37823 37825 like clerks

like/love 42739 42741 like generator

like/love 46982 46984 like mud

like/love 49375 49377 like branches

like/love 67580 67582 like sheep

Additionally, Spacy can be combined with regular expressions to create even more complex searches, but will not be shown here. Please consult Spacy’s documentation in case you want to build more complex search patterns.

22.10. Chapter Summary and Outlook#

Throughout this chapter, we delved into the world of Natural Language Processing (NLP), exploring several key techniques for handling and processing text data effectively:

Cleaning: This is often the first step in processing text data, involving tasks like removing URLs, Emojis, and special characters, or replacing unwanted line breaks (

"\n").Tokenization: This involves breaking down text into smaller parts called tokens. Tokens can be as small as individual words or can even correspond to sentences or paragraphs, depending on the level of analysis required.

Stemming: Words can appear in different forms depending on gender, number, person, tense, and so on. Stemming involves reducing these words to their root or stem form. For example, the word “finding” could be stemmed to “find”. This process is heuristic and sometimes may lead to non-meaningful stems.

Lemmatization: Similar to stemming, lemmatization aims to reduce words to their base form, but with a more sophisticated approach that takes vocabulary and morphological analysis into account. Lemmatization ensures that only the inflectional endings are removed, thus isolating the canonical form of a word known as a lemma. For example, “found” would be lemmatized to “find”.

Other Operations: These could include removing numbers, punctuation marks, symbols, and stop words (commonly used words like “and”, “the”, “a”, etc.), as well as converting text to lowercase for uniformity.

We’ve also discussed the application of these concepts using powerful Python libraries like NLTK and SpaCy, which provide intuitive and efficient tools for dealing with NLP tasks.