6. Functions#

We have already used functions like print(), type(), and even int() or str().

These functions are built into Python.

Most of the functions we will use, however, will either be:

written (or: defined) by us, or

imported (loaded).

We will cover both cases.

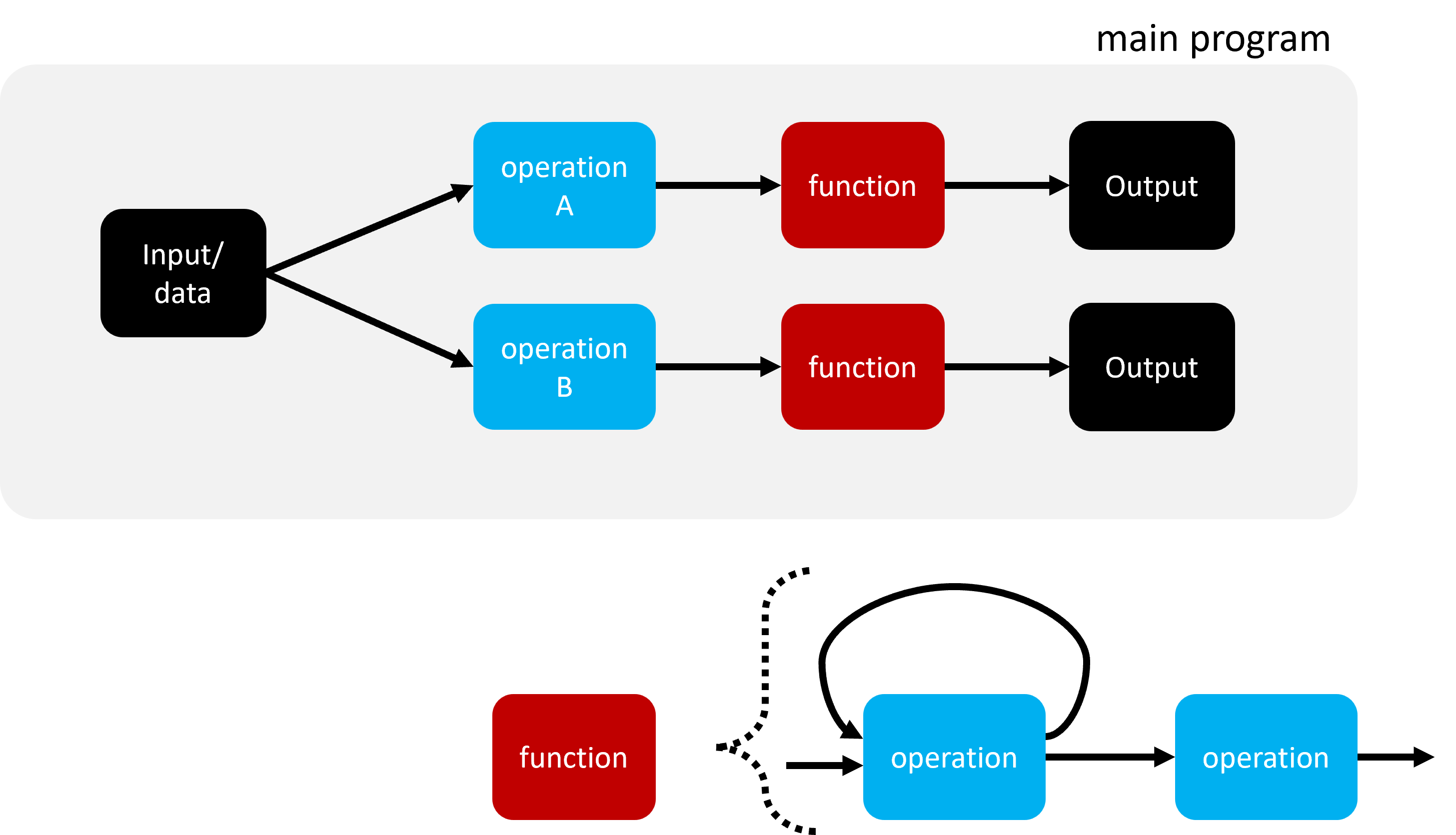

Functions play a crucial role in creating more complex programs. They allow us to structure extensive workflows in a more logical and readable manner.

6.1. Defining Functions#

def good_thing():

print("Written once...")

print("... used 1,000 times!")

print("Saved three lines of code again.")

When we run this code, nothing happens initially!

Functions only execute when explicitly called:

good_thing()

This function does not return anything (only prints) and does not require arguments.

The general structure of functions is as follows:

def function_name(parameter1, parameter2, etc):

# code

return result

It’s even better to include a docstring, which serves as the basic documentation for the function. This can describe the function and its parameters, as well as provide examples or references.

def function_name(parameter1, parameter2, ...):

"""Description of the function.

"""

# code

return result

Functions can also have no parameters (e.g., good_thing() above).

Additionally, you can set default values for parameters, which are used if no new values are provided when the function is called.

def function_name(p1, p2=3.1415):

"""Description of the function.

"""

... code ...

return result

Here’s another example of a simple function with two parameters:

def x_vs_y(x, y):

"""Compare the numbers x and y."""

if x == y:

print("They are equal!")

elif x > y:

print(f"{x} is bigger than {y}")

else:

print(f"{x} is smaller than {y}")

x_vs_y(10, 70) # => 10 is smaller than 70

x_vs_y(0.000001, 1e-5) # => 1e-06 is smaller than 1e-05

But the following will not work:

x_vs_y(10) # => TypeError: x_vs_y() missing 1 required positional argument: 'y'

6.1.1. Default Values#

Here’s an example of a function where one of the two parameters has a default value:

def boxes_to_eggs(n_boxes, eggs_per_box=6):

"""Compute the total number of eggs in n_boxes boxes."""

return n_boxes * eggs_per_box

print(boxes_to_eggs(5)) # => 30

print(boxes_to_eggs(5, 10)) # => 50

print(boxes_to_eggs(5, eggs_per_box=10)) # => 50

print(boxes_to_eggs(eggs_per_box=10, n_boxes=5)) # => 50

However, this is not allowed:

print(boxes_to_eggs(n_boxes=5, 10)) # => SyntaxError: positional argument follows keyword argument

6.1.2. Optional: Parameter Order Matters#

With more parameters, the order becomes even more critical. Accidental mix-ups may result in functional but incorrect code:

def boxes_to_eggs(n_boxes, eggs_per_box=6, broken_eggs_per_box=0):

"""Compute the total number of eggs in n_boxes boxes."""

return int(n_boxes * (eggs_per_box - broken_eggs_per_box))

print(boxes_to_eggs(5)) # => 30

print(boxes_to_eggs(5, 10)) # => 50

print(boxes_to_eggs(5, broken_eggs_per_box=0.25)) # => 25

But consider this:

print(boxes_to_eggs(5, 10, 0.25)) # => 48

print(boxes_to_eggs(5, 0.25, 10)) # => -48 !!!

MINI Quiz

A function returns values/data to the program using…

a)

b)return

c)out

d)assertA function without a

returnstatement returns…

a) Nothing

b) The parameters

c) The variables

d)None

6.1.3. Return: Something Always Comes Back#

As we’ve seen, many functions contain a return statement. This does two things: it terminates the function’s execution and returns one or more values (e.g., return variable1, variable2).

However, functions don’t require a return statement. For example:

def double_print(input_str):

print(2 * input_str)

double_print("Hello World!") # --> Hello World!Hello World!

In Python, every function returns a value. If no return is specified, it implicitly returns None:

result = print("hello")

print(result) # --> None

6.1.3.1. Return Doesn’t Have to Be at the End#

A function can have multiple return statements, and they don’t have to be at the end:

def pick_smallest(a, b):

if a > b:

return b

if a < b:

return a

print("They look alike!")

6.1.4. Namespaces#

A namespace is an area within a program where a name (e.g., variables, functions) is valid. Python has three main types of namespaces:

Local scope: Valid within a function or method.

Global scope: Valid throughout the program or interpreter session.

Built-in scope: Names defined by Python itself.

Examples:

a = 5

b = 7

def do_stuff():

return a + b

result = do_stuff()

print(a, b, result) # => 5 7 12

Local and global variables behave differently:

a = 5

def do_stuff():

a = 1000

return a

print(do_stuff()) # => 1000

print(a) # => 5

Global variables are not recommended for modification within functions, as it can lead to unclear and buggy code. Instead, explicitly pass variables as function parameters:

def do_stuff(a):

a = a * 2

return a

do_stuff(10) # => 20

6.1.5. Mutable and Immutable Data Types#

Mutable objects (e.g., lists, dictionaries) can be modified within functions:

def modify_list(my_list):

my_list.append(42)

lst = [1, 2, 3]

modify_list(lst)

print(lst) # => [1, 2, 3, 42]

Immutable objects (e.g., integers, tuples) cannot:

def modify_value(a):

a = a * 2

x = 10

modify_value(x)

print(x) # => 10

In the next section, we’ll explore more advanced function types.